Photo's,video's,biographies and articles detailing a few of the important people and places in the religion of Islam.

Thursday, October 28, 2010

Sunday, October 24, 2010

Omar ibn Said (1770-1864)

Omar ibn Said (1770-1864)

was born in present-day Senegal in Futa Tooro, a region between the Senegal River and Gambia River in West Africa, to a wealthy family. He was an Islamic scholar and a Fula who spent 25 years of his life studying with prominent Muslim scholars in Africa. In 1807, he was captured during a military conflict, enslaved and taken across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States. He escaped from a cruel master in Charleston, South Carolina, and journeyed to Fayetteville, North Carolina. There he was recaptured and later sold to James Owen. Said lived into his mid-nineties and was still a slave at the time of his death in 1864. He was buried in Bladen County, North Carolina. Omar ibn Said was also known as Uncle Moreau and Prince Omeroh.In 1991, a masjid in Fayetteville, North Carolina renamed itself Masjid Omar Ibn Said in his honor.

Add a caption

Omar ibn Said (1770-1864)

was born in present-day Senegal in Futa Tooro, a region between the Senegal River and Gambia River in West Africa, to a wealthy family. He was an Islamic scholar and a Fula who spent 25 years of his life studying with prominent Muslim scholars in Africa. In 1807, he was captured during a military conflict, enslaved and taken across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States. He escaped from a cruel master in Charleston, South Carolina, and journeyed to Fayetteville, North Carolina. There he was recaptured and later sold to James Owen. Said lived into his mid-nineties and was still a slave at the time of his death in 1864. He was buried in Bladen County, North Carolina. Omar ibn Said was also known as Uncle Moreau and Prince Omeroh.In 1991, a masjid in Fayetteville, North Carolina renamed itself Masjid Omar Ibn Said in his honor.

Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (1701–1773)

Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (1701–1773),

was a famous Muslim slave who was a victim of the Atlantic slave trade. Born in Bondu, Senegal West Africa, Ayuba's memoirs were published as one of the earliest slave narratives

While in captivity, Ayuba used to go into the woods to pray. However, after being humiliated by a child while praying, Ayuba chose to run away. He was captured and imprisoned at the Kent County Courthouse. It was there that he was discovered by a lawyer, Thomas Bluett, traveling through on business.

The lawyer was impressed by Ayuba's ability to write in Arabic. In the narrative, Bluett writes the following:

Upon our Talking and making Signs to him, he wrote a Line or two before us, and when he read it, pronounced the Words Allah and Mahommed; by which, and his refusing a Glass of Wine we offered him, we perceived he was a Mahometan, but could not imagine of what Country he was, or how he got thither; for by his affable Carriage, and the easy Composure of his Countenance, we could perceive he was no common Slave."

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ayuba_Suleiman_Diallo

Monday, October 11, 2010

Sunday, October 10, 2010

Saturday, October 9, 2010

Thursday, October 7, 2010

Tuesday, October 5, 2010

Monday, October 4, 2010

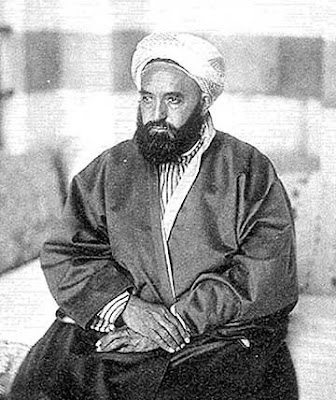

Amir Abd al-Qādir al-Jazā'irī

Amir Abd al-Qādir al-Jazā'irī

عبد القادر ابن محي الدي

Amir Abd al-Qādir was born near the town of Mascara near Oran, in 1807 or 1808. His father, Muhyi al-Din al-Hasani, was a shaykh in the Qadiri Tariqa. He was a Banu Ifran Berber and descendent from the Prophet Muhammad(saw).

In his childhood he memorized the Qur'an and was trained in horsemanship, theology and linguistics, and received an education far better than that of his peers. In 1825, he set out for the Muslim pilgrimage, hajj, with his father. While in Mecca, he encountered Imam Shamil; the two spoke at length on different topics. He also traveled to Damascus and Baghdad, and visited the graves of noted Muslims, such as Shaykh Ibn Arabi and Sidi Abdal Qader al Jilani named also El-Jilali in Algeria. He returned to his homeland a few months before the arrival of the French.

In 1830, Algeria was invaded by France; French colonial domination over Algeria supplanted what had been domination in name only by the Ottoman Empire. Within two years, `Abd al-Qādir was made an amir and with the loyalty of a number of tribes began a rebellion against the French. He was effective at using guerrilla warfare and for a decade, up until 1842, scored many victories. He often signed tactical truces with the French, but these did not last. His power base was in the western part of Algeria, where he was successful in uniting the tribes against the French. He was noted for his chivalry; on one occasion he released his French captives simply because he had insufficient food to feed them. Throughout this period `Abd al-Qādir demonstrated political and military leadership, and acted as a capable administrator and a persuasive orator. His fervent faith in the doctrines of Islam was unquestioned, and his ultimate failure was due in considerable measure to the refusal of the Kabyles, Berber mountain tribes, to make common cause with the Arabs against the French.

Until the beginning of 1842 the struggle went in his favor; however, the resistance was put down by Marshal Bugeaud. In 1837, `Abd al-Qādir signed the Treaty of Tafna with Bugeaud, in which he recognized France's sovereignty in Oran and Algiers, while France recognized his control over the remaining two-thirds of the country, mainly the interior. When French troops marched through a mountain pass in territory `Abd al-Qādir claimed as his in open defiance of that claim, he renewed the resistance on October 15, 1839.

Amir Abd Al-Qādir was ultimately forced to surrender. The French armies grew large, and brutally suppressed the native population and practiced a scorched-earth policy.

Amir Abd Al-Qādir's failure to get support from eastern tribes, apart from the Berbers of western Kabylie, also contributed to the quelling of the rebellion. On December 21, 1847, after being denied refuge in Morocco (strangely parallelling Jugurtha's career two thousand years earlier) because of French diplomatic and military pressure on its leaders, `Abd al-Qādir surrendered to General Louis de Lamoricière in exchange for the promise that he would be allowed to go to Alexandria or Acre. Two days later, his surrender was made official to the French Governor-General of Algeria, Henri d'Orléans, duc d'Aumale. The French government refused to honour Lamoricière's promise and `Abd Al-Qādir was exiled to France.

Abd Al-Qādir and his family were detained in France, first at Toulon, then at Pau, and in November 1848 they were transferred to the château of Amboise. There he remained until October 1852, when he was released by Napoléon III and given an annual pension of 100 000 francs on taking an oath never again to disturb Algeria. He then took up residence in Bursa, moving in 1855 to Damascus. He devoted himself anew to theology and philosophy, and composed a philosophical treatise, of which a French translation was published in 1858 under the title of Rappel à l'intelligent. Avis à l'indifférent. He also wrote a book on the Arabian horse.

While in Damascus he befriended Jane Digby and Richard and Isabel Burton. In July 1860, conflict between the Druze and Maronites of Mount Lebanon spread to Damascus, and local Druze attacked the Christian quarter, killing over 3,000 persons. `Abd al-Qādir and his personal guard saved large numbers of Christians, bringing them to safety in his house and in the citadel. For this action the French government increased his pension to 4000 Louis and bestowed on him the Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur. He was also honoured by Abraham Lincoln for this gesture towards Christians with several guns that are now on display in the Algiers museum.

In 1865 he visited Paris on the invitation of Napoléon III and was greeted with both official and popular respect.

Amir Abd Al-Qādir died at Damascus on 26 May 1883 and was buried near the great sufi Ibn Arabi in Damascus.

Abd al-Qādir is recognized and venerated as the first hero of Algerian independence. His green and white standard was adopted by the Algerian liberation movement during the War of Independence and became the national flag of independent Algeria. He was buried in Damascus in the same mausoleum as Ibn Arabi, until the Algerian government brought his remains back to Algeria to be interred with much ceremony on 5 July 1966, the fourth anniversary of independence and the 136th anniversary of the French conquest. The Emir Abdel Kader University and a mosque bearing his name were constructed as a national shrine in Constantine, Algeria.

An indication of the international fame of Abd al-Qādir's struggle is given by the way that the town of Elkader, Iowa in the United States came to be named after him. When the new community was being officially planned, on what was then the American frontier, founders Timothy Davis, John Thompson and Chester Sage—none of them Arabs or Muslims—were so impressed with what they heard of the Algerian leader's valiant struggle that they decided to name the new town for him. The American town has retained its Algerian connection by establishing a sister city connection with Mascara, Algeria.

His notable children and grandchildren:

Amir Muhammad ibn Abd al-Qadir al-Jazairi

Amir Said al-Jazairi, who took over government affairs of Syria when the Ottomans evacuated on 28 September 1918 and stayed in office until the Arab Army entered Damascus on 1 October 1918.

Baseball statistician and sportswriter Rany Jazayerli claims to be the great-great-great-great nephew of Abd al-Qādir

Add a caption

Amir Abd al-Qādir al-Jazā'irī

عبد القادر ابن محي الدي

Amir Abd al-Qādir was born near the town of Mascara near Oran, in 1807 or 1808. His father, Muhyi al-Din al-Hasani, was a shaykh in the Qadiri Tariqa. He was a Banu Ifran Berber and descendent from the Prophet Muhammad(saw).

In his childhood he memorized the Qur'an and was trained in horsemanship, theology and linguistics, and received an education far better than that of his peers. In 1825, he set out for the Muslim pilgrimage, hajj, with his father. While in Mecca, he encountered Imam Shamil; the two spoke at length on different topics. He also traveled to Damascus and Baghdad, and visited the graves of noted Muslims, such as Shaykh Ibn Arabi and Sidi Abdal Qader al Jilani named also El-Jilali in Algeria. He returned to his homeland a few months before the arrival of the French.

In 1830, Algeria was invaded by France; French colonial domination over Algeria supplanted what had been domination in name only by the Ottoman Empire. Within two years, `Abd al-Qādir was made an amir and with the loyalty of a number of tribes began a rebellion against the French. He was effective at using guerrilla warfare and for a decade, up until 1842, scored many victories. He often signed tactical truces with the French, but these did not last. His power base was in the western part of Algeria, where he was successful in uniting the tribes against the French. He was noted for his chivalry; on one occasion he released his French captives simply because he had insufficient food to feed them. Throughout this period `Abd al-Qādir demonstrated political and military leadership, and acted as a capable administrator and a persuasive orator. His fervent faith in the doctrines of Islam was unquestioned, and his ultimate failure was due in considerable measure to the refusal of the Kabyles, Berber mountain tribes, to make common cause with the Arabs against the French.

Until the beginning of 1842 the struggle went in his favor; however, the resistance was put down by Marshal Bugeaud. In 1837, `Abd al-Qādir signed the Treaty of Tafna with Bugeaud, in which he recognized France's sovereignty in Oran and Algiers, while France recognized his control over the remaining two-thirds of the country, mainly the interior. When French troops marched through a mountain pass in territory `Abd al-Qādir claimed as his in open defiance of that claim, he renewed the resistance on October 15, 1839.

Amir Abd Al-Qādir was ultimately forced to surrender. The French armies grew large, and brutally suppressed the native population and practiced a scorched-earth policy.

Amir Abd Al-Qādir's failure to get support from eastern tribes, apart from the Berbers of western Kabylie, also contributed to the quelling of the rebellion. On December 21, 1847, after being denied refuge in Morocco (strangely parallelling Jugurtha's career two thousand years earlier) because of French diplomatic and military pressure on its leaders, `Abd al-Qādir surrendered to General Louis de Lamoricière in exchange for the promise that he would be allowed to go to Alexandria or Acre. Two days later, his surrender was made official to the French Governor-General of Algeria, Henri d'Orléans, duc d'Aumale. The French government refused to honour Lamoricière's promise and `Abd Al-Qādir was exiled to France.

Abd Al-Qādir and his family were detained in France, first at Toulon, then at Pau, and in November 1848 they were transferred to the château of Amboise. There he remained until October 1852, when he was released by Napoléon III and given an annual pension of 100 000 francs on taking an oath never again to disturb Algeria. He then took up residence in Bursa, moving in 1855 to Damascus. He devoted himself anew to theology and philosophy, and composed a philosophical treatise, of which a French translation was published in 1858 under the title of Rappel à l'intelligent. Avis à l'indifférent. He also wrote a book on the Arabian horse.

While in Damascus he befriended Jane Digby and Richard and Isabel Burton. In July 1860, conflict between the Druze and Maronites of Mount Lebanon spread to Damascus, and local Druze attacked the Christian quarter, killing over 3,000 persons. `Abd al-Qādir and his personal guard saved large numbers of Christians, bringing them to safety in his house and in the citadel. For this action the French government increased his pension to 4000 Louis and bestowed on him the Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur. He was also honoured by Abraham Lincoln for this gesture towards Christians with several guns that are now on display in the Algiers museum.

In 1865 he visited Paris on the invitation of Napoléon III and was greeted with both official and popular respect.

Amir Abd Al-Qādir died at Damascus on 26 May 1883 and was buried near the great sufi Ibn Arabi in Damascus.

Abd al-Qādir is recognized and venerated as the first hero of Algerian independence. His green and white standard was adopted by the Algerian liberation movement during the War of Independence and became the national flag of independent Algeria. He was buried in Damascus in the same mausoleum as Ibn Arabi, until the Algerian government brought his remains back to Algeria to be interred with much ceremony on 5 July 1966, the fourth anniversary of independence and the 136th anniversary of the French conquest. The Emir Abdel Kader University and a mosque bearing his name were constructed as a national shrine in Constantine, Algeria.

An indication of the international fame of Abd al-Qādir's struggle is given by the way that the town of Elkader, Iowa in the United States came to be named after him. When the new community was being officially planned, on what was then the American frontier, founders Timothy Davis, John Thompson and Chester Sage—none of them Arabs or Muslims—were so impressed with what they heard of the Algerian leader's valiant struggle that they decided to name the new town for him. The American town has retained its Algerian connection by establishing a sister city connection with Mascara, Algeria.

His notable children and grandchildren:

Amir Muhammad ibn Abd al-Qadir al-Jazairi

Amir Said al-Jazairi, who took over government affairs of Syria when the Ottomans evacuated on 28 September 1918 and stayed in office until the Arab Army entered Damascus on 1 October 1918.

Baseball statistician and sportswriter Rany Jazayerli claims to be the great-great-great-great nephew of Abd al-Qādir

Friday, October 1, 2010

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)